A post by

Lucia Baier

Content Manager

YONTEX GmbH & Co. KG

Few people may realize it, but distillation has long been an integral part of human history. It has not only fundamentally changed the processing of crude oil, but has also influenced how and what kind of alcohol people consume for centuries. The distillation process is simple in principle, but quite complicated in practice and in its various applications. This article will therefore address the following questions: What is distillation? And how is the distillation of alcohol carried out?

Released on 16/08/2021Updated on 05/07/2024

A post by

Lucia Baier

Content Manager

YONTEX GmbH & Co. KG

Put simply, distillation is the process of separating two components of a liquid. It is also possible to separate several components using fractional distillation. In this process, the initial mixture or liquid is first brought to boiling point. Because the different components have different boiling points, the element that is to be extracted can be converted into a gaseous state.

A condenser cools the gas or vapour and converts the distillate back into a liquid. The result still contains several components of the original liquid, but the composition differs from the initial mixture. To improve the purity of the product, the process is usually repeated.

Distillation is mainly used to process crude oil in a refinery (fractional distillation), to distil alcohol or to distil water, with this article focussing on alcohol distillation. The advantage of this type of separation of individual elements is that no further additives or chemicals are required to achieve the desired result.

The key to alcohol as used in the beverage industry is alcoholic fermentation. Alcohol is produced from starch or sugar. A lack of oxygen and bacteria or yeast drive the fermentation process. This is the case in the production of beer and wine, for example. A further step takes place during the distillation of spirits.

Spirits are distilled from a mash. This is a mixture of fruit pulp, juice, peel and seeds, which also contains sugar or starch. According to the information page of the German customs authorities, the mash can consist of the following raw materials:

The alcohol produced by fermentation within the mash needs to be distilled. This means that only the volatile elements such as alcohol, water and flavourings change their physical state and turn into vapour.

The seeds, pulp and skins are left behind. Glycerine, succinic acid, amino and fruit acids as well as other harmful by-products created during the fermentation and metabolic process are removed.

Different distillation processes are used to extract the alcohol, which produce equally different results.

A terracotta distillation apparatus is the earliest known evidence of distillation. This comes from an Indus valley in Pakistan and is dated to around 3000 BC.

The first distillation devices looked very simple: They consisted of a container and a lid. The distilled condensate settled on the lid and was soaked up with sponges or wool and later wrung out. In this way, the distilled liquid did not drip back into the original material or otherwise get lost.

Even in the Neolithic Age, people distilled pitch and sulphur to seal ships. The process was also used to produce adhesives and remedies. It is assumed that distillation was used early on for perfume production and that essential oils were produced using this method in ancient times. According to Aristotle, the Greeks used distillation to produce wines and even drinkable water from seawater in the 4th century BC.

In ancient Egypt, the introduction of the distilling helmet signalled something of a technical advancement. However, alcohol was not produced during this time because there were no suitable cooling methods. Because the boiling point of alcohol is 78.3 degrees Celsius, this component evaporated during the distillation process. Only substances with a higher boiling point than water could be separated.

The Persian chemist Abu Musa Jābir ibn Hayyān and the Iranian physician and scientist Abu Bakr Mohammed Ibn Zakariya al-Razi advanced many chemical processes and also distillation in the 9th century AD. The latter even wrote down his techniques and methods, which are still relevant today, in one of the first textbooks on chemistry.

In the Middle Ages, scientists - also known as alchemists - were able to develop a cooling process for alcohol production using cooled pipes. The resulting product, known as "fiery water", was still highly diluted.

Even then, however, it was discovered that a purer alcohol product could be obtained from several successive distillation processes.

From then until the 19th century, alcohol was used for both medicinal and recreational purposes. During the plague period from 1347 to 1350, many people even produced their own alcohol. This went so far that laws had to be passed to prevent drunkenness.

Commercial alcohol production in Europe first began in the 15th century. Popular wines, fermented apple juices, cognacs and brandies were produced in the south of France in particular, which consumers still enjoy today. The development of alcohol production did not stand still in Amsterdam in the Netherlands either. It was here that Lucas Bols first used the peat-heated still in 1575.

In the years and centuries that followed, this technology for producing alcohol was to be refined further and further, from automation processes to the use of artificial intelligence. And even though improved alcohol products with new and interesting flavours are constantly being developed, the basic chemical principle remains the same today.

In general, distillation can be divided into two different methods: continuous and discontinuous distillation. These two methods in turn have different distillation techniques.

This distillation process is particularly suitable for the mass production of spirits. In this process, mash is added without interruption for continuous distillation. However, there is only one specific distillation process, which goes by various names:

Distillation is carried out using a patented or Coffey distillation apparatus, which consists of several copper columns and is therefore also known as a column apparatus.

Even though the distillation process is now two centuries old, countless types of this plant design exist today. The reason for its popularity is that spirits can be produced quickly and inexpensively using this type of system and method. These include vodka and whisky as well as many other popular drinks.

Smaller column stills consist of two, larger ones of several stainless steel columns (the German translation of Column is Säule). There are numerous variations with different sizes. The diameters range from 16 to 96 inches. There is often no bulbous pot design as with other distillation systems (see pot still process).

To start the distillation process, the manufacturer fills the substance to be distilled into the first column, also known as the rectification column or rectifier. Here it passes downwards through a screw tube and is simultaneously heated by a vapour jet emanating from the bottom.

The liquid produced here flows from the rectifier into the second column, which is known as the analyser. This contains several copper trays with holes through which the liquid flows. With the help of gravity, it flows downwards through these plates. In this column, water vapour also ensures that the ethanol and aroma components volatilise and separate from the mash.

The vapours rise upwards and are channelled back through the bottoms of the column - each subsequent plate is slightly cooler than the one below. Condensation therefore occurs on each of these plates. Because hot vapours are constantly flowing through the system, the vapour always turns into liquid and then back into vapour. This therefore leads to an increase in the purity of the spirit.

While the mash residue is drained off at the bottom of the second column, the alcohol-containing vapour is fed back into the first column, where the vapour is cooled down again. During the distillation process, different boiling points produce liquids that can be divided into pre-run, mid-run and post-run and are differentiated as follows:

Depending on the type of alcohol or spirit to be produced, the pre-run and mid-run can be added back to the mash so that distillers can distil them again.

Even if the distillation process sounds simple in principle, skilled workers must constantly monitor the process. A small change in the flow rate can have a major impact on the alcohol level, cooling and ultimately the quality of the end product.

As the name suggests, spirits producers do not constantly add new mash during discontinuous distillation. Instead, they only fill the still with portions to distil alcohol. Discontinuous distillation can be further subdivided into double distillation, single distillation and the pot still method.

A still for discontinuous distillation usually consists of the following components:

The still is a heatable vessel that is heated directly by a burner or indirectly either by steam or a water bath. Manufacturers usually fill the mash through an opening and empty it again through a flap after the distilling process.

An agitator helps to mix the mash and ensure even and constant heating so that the mash cannot burn. This also enables precise separation of the individual elements during alcohol distillation.

The alcohol gases collect in the spirit helmet above the still, which are channelled into the booster unit via the spirit tube during a simple firing. Water condensation takes place in the rectification column, which in turn leads to a high alcohol content.

The alcohol vapours rise to the dephlegmator. Here the temperatures are above the boiling point of the alcohol, but still below the boiling point of water. In this way, an even higher concentration of alcohol can be distilled.

For stone fruit mashes, a catalyst is usually required to filter ethyl carbamate or hydrocyanic acid out of the distillate. However, this can usually be excluded from the distillation process if it is not necessary.

The vapour is ultimately cooled in a counterflow cooler. Cooling water in cooling pipes absorbs the heat from the alcohol gas. The vapour condenses and the distillate is collected in a long container, also known as a receiver.

In this process, producers carry out two or three firing cycles. The product of the first distillation – also known as raw or raw spirit – still contains alcohol, flavourings and fusel oil. A second distillation – the so-called fine distillation – is now necessary to create a product that is edible and not harmful to health.

Finally, the careful increase in temperature during distillation results in three stages:

Manufacturers must be extremely careful during this process and only increase the temperature slowly. This is the only way to guarantee that only the undesirable elements and not the desired flavourings are eliminated after the pre-run.

At the beginning of the middle run, the distillate contains 70 to 80 per cent alcohol. After the fine distillation, it is 50 to 55 per cent for stone fruit and 45 to 50 per cent for pome fruit. With 100 litres of rough spirit, 25 to 35 litres of fine spirit can be produced.

In simple distillation, only mash is used as the basis. The process is comparable to fine distillation in the double distillation process. However, the result is a product with a lower alcohol content and a higher flavour content. However, a rectification column can increase the alcohol content again.

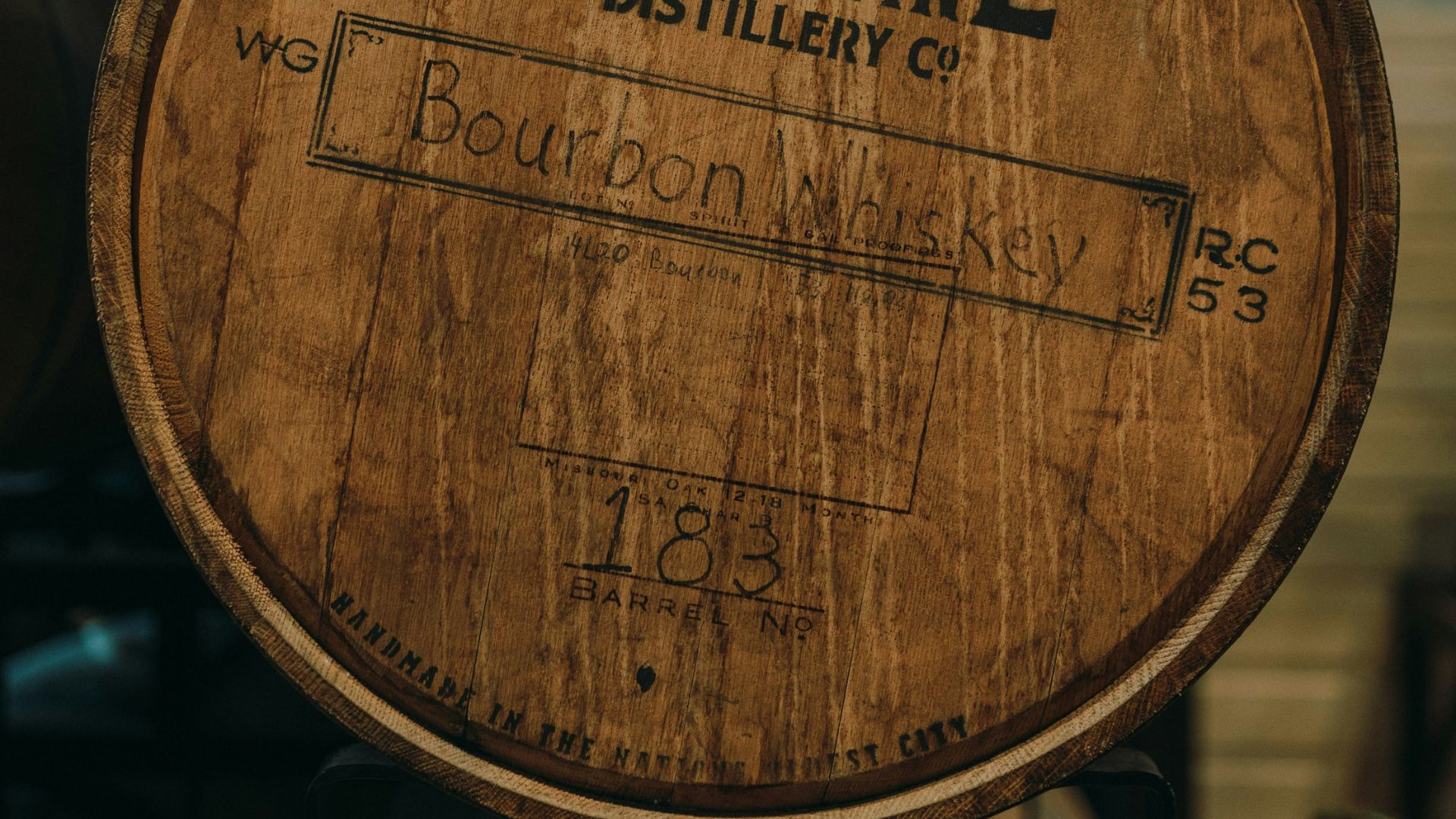

Distilleries use the pot still method to produce Scottish malt whiskey or Irish bourbon whiskey and pot still whiskey. This is one of the oldest ways of producing spirits.

In this traditional method, the pot still or still is heated from below with the raw material to be distilled. This pot still looks like a pot on four legs. It is usually made of copper or stainless steel. The shape of the pot is quite bulbous and large at the bottom. Towards the top it becomes narrower and narrower and turns into a thin tube, also known as a swan neck or Lyne arm, because it used to look curved - but is now straight.

This neck leads to the condenser, a spiral-shaped tube located inside a cylindrical container filled with cold water. The vapours therefore move from the pot via the swan neck through the spiral and are cooled by the water. They condense slowly and return to a liquid form as soon as they reach the end of the spiral.

Distillation in the pot still process often requires two runs because the resulting final liquid is often quite low in alcohol. This distillate is known as low wine in whiskey production and brouillis in cognac production.

After the first batch, the still is cleaned and the distillate is distilled again. The process is obviously very complex and is therefore not suitable for mass production. Nevertheless, some forms of alcohol require this special type of distillation in order to maintain a certain integrity.

Ultimately, it is the combination of the right raw materials and process technology that determines whether a distillate is good or not.

Theoretically, distillation can also be used for dealcoholisation. In practice, however, this is more difficult because the temperatures required for this can also affect the flavour of the end product. So if someone wants to distil schnapps or distil wine, simple distillation may not only eliminate the alcohol, but also the flavourings.

An alternative is reverse osmosis or osmotic distillation. Water and alcohol are passed through a membrane. All other elements, also known as retentate, to which the flavourings belong, remain in front of the membrane. Distillation separates the alcohol from the water. The latter is mixed with the other elements. The result is a beverage with a reduced alcohol content, but which still has the original flavour qualities.

Vacuum distillation is another option for dealcoholisation. Here, the boiling point of the alcohol is lowered using low air pressure. In this way, the alcohol is separated from the drink, while the flavourings remain relatively unaffected.

Quality assurance

A post by Dr. Jürgen Hofmann

Process control

A post by Klaus Vette

Automatisation

A post by Helmut Brunner

Raw material supply

A post by Horst Dornbusch